It’s Thursday, and today we’re discussing Elevarm, an Indonesian agritech startup that raised $4.25 million in a pre-Series A round from Intudo, Insignia Ventures Partners and 500 Global.

The Product

Elevarm is a horticulture-focused agritech company aiming to help Indonesian farmers grow more efficiently and sustainably.

Here’s the premise. Farmers struggle on multiple fronts: they don’t have the knowledge to maximize their soil’s potential, they lack access to financing, they often use suboptimal seeds and fertilizers, and their distribution channels are weak.

Elevarm is trying to tackle all of that. It offers a holistic approach to improving farm productivity while making the value chain more transparent and sustainable.

The company’s offering is a bit sprawling, but we can break it down into three broad categories.

Soil inputs

This covers everything that goes into the soil. It falls under the umbrella of NextBio, which includes soil testing, supplying high-quality seeds, and providing fertilizers.

Klinik Tani is Elevarm’s testing service. Through it, farmers can understand the microbial content of their soil and plants—basically figuring out how to fertilize, prevent disease, or treat it properly.

They also produce Vermicomplus, a vermicompost fertilizer made from cow manure decomposed by earthworms. Elevarm claims this product boosts plant growth by 40% and cuts fertilization costs by 42%.

Farmers can manage all of this using the Elevarm app—it lets them monitor their land, manage workers (if they have any), and trade their harvest.

And if they get stuck, there’s advisory support: training, land visits, and other services. Think of it as consulting for farmers. Elevarm helps with everything from land prep to budgeting to choosing commodities and processing.

All in all, Elevarm is:

Helping farmers figure out which crops suit their specific conditions.

Making farming more efficient through better inputs and practices.

Supporting farmers at every stage so they can make the most of their land

Distribution

This part includes both collecting the harvest and selling it.

Harvest collection happens through Tikum, a network of hubs where crops are gathered, sorted, graded, and packaged. Right now, it’s focused on chili farmers, but there’s a good chance it’ll expand to other crops. Here, Elevarm tackles unfair pricing—by simply paying farmers more.

Then there’s PasarAgri, a trading platform for wholesalers to buy directly from farmers. It’s not revolutionary in how it works, but it’s a necessary component of the value chain.

Financing

Elevarm doesn’t just provide loans. In fact, they don’t have pure cash loans, instead they provide what’s called productive financing, which is a loan for a specific purpose, in this case—buying seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers. Also, a loan from Elevarm is packaged with life and crop insurance. Additionally, the company contributes premiums for crop insurance, thus reinforcing protection against natural disasters, droughts, etc. Finally, there’s no penalty for late payments—the loan is simply restructured.

The company offers financing to trading partners, as well as wholesalers. The latter, for example, can use a buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) option for large orders.

The Business Model

Two key aspects of Elevarm’s business model I want to highlight.

Elevarm as an ecosystem

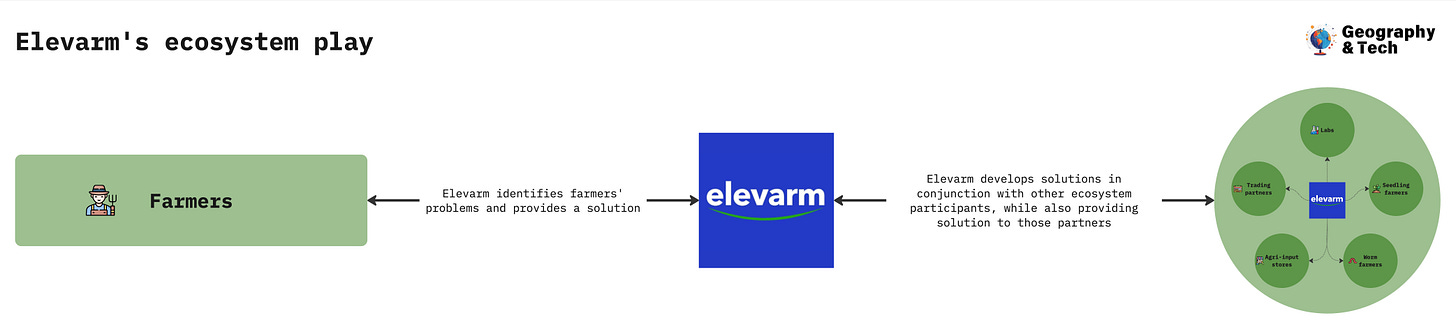

First, Elevarm is building an ecosystem. Let’s call it a hub-and-root ecosystem (shoutout to ChatGPT for the name).

The root in this case is the farmers—they are the foundation of Elevarm’s business. Farmers’ pain points trigger Elevarm’s product development. By developing products for farmers, Elevarm uncovers the pain points of all the supporting players. It then connects the two pain points, thus hitting two targets with one arrow.

Let’s look at two specific examples.

Vermicompost production. Meanwhile, worm farmers—yes, that’s a thing—breed worms for uses like fish feed and pharmaceuticals. These worms feed on cow manure, which worm farmers buy from cattle farmers. But managing manure supply is tricky, and excess manure often goes to waste. Elevarm steps in and teaches worm farmers to make vermicompost instead. If you want to acquire that knowledge too, here’s how.

Vermicompost purchasing. You hear vermicompost is great. Where do you get it? Your current fertilizer seller knows you hate chicken dung—it stinks and takes space—so they start looking for better options. And that’s the wholesale demand for Elevarm’s vermicompost.

At a higher level, Elevarm plays three interlinked roles:

Enabler—Provides products that empower participants across the ecosystem to do more or be more efficient.

Connector—Bridges fragmented ecosystem players and helps them work together.

Guide—Stays close to farmers and helps them through obstacles.

From start to finish, Elevarm is there for the farmer. While the focus is upstream, the company’s potential downstream shouldn’t be underestimated.

Elevarm as a trusted partner

Second—and this is as much about the business model as it is about the company’s philosophy—Elevarm is trying to be a trusted partner.

Every product they offer targets a real, painful issue. These aren’t “too many emails” problems. These are “I can barely survive on my harvest” problems. Yes, Elevarm is committed to ESG, but you get the sense they’d be doing the same work even without those labels. The drop in farmers living below the poverty line—from 74% in 2021 to 32% in 2023—is a strong signal.

Transparency is also core. A lot of the information I’ve provided thus far comes from their sustainability report. And it’s not just PR fluff. They do acknowledge where there’s room to grow, things like “our potato productivity sucks and we need to improve.”.

In a business sense, this approach manifests itself in the following way.

On the one hand, the company doesn’t maximize revenue from each part of the farmer’s journey.

On the other, by always supporting the farmer—by being there for them on a consistent basis—they build real trust. Product managers going to farms, farmer meetings four times a month—these are not some nebulous activities. This is the deliberate building of a long-term relationship.

So there’s no need to maximize profit here today, because the lifetime value of a client farmer could span decades.

So how does the company make money?

While Elevarm is focused on impact, it’s still a business. Here’s how they generate revenue:

Loan interest: 2–3% per month, depending on the crop

Product sales: Vermicomplus and biostimulants sold directly and wholesale. Farmer sales include a 5–10% premium to cover advisory services.

Reselling: They resell produce to wholesalers, retailers, and other trading partners

That’s all the detail we’ve got for now, but I’ll update the article if more surfaces.

The Local Angle

Indonesia and agriculture

Let’s start with a bland statement: agriculture is important for Indonesia. But it really is—and in several ways:

It employs 29.3% of the workforce. Although that figure has been steadily falling, that’s still over 40 million people.

It dedicates a lot of land to agriculture. Among the 15 countries with the most cultivated landmass, only 4 rank higher in terms of the percentage of land used for agriculture.

It contributes 24.1% to Indonesia’s exports. Not quite Brazil levels (which is over 40%), but actually the second-highest among countries with populations over 50 million.

And as we learned last week, Indonesia produces the second-most diverse food selection in the world—behind only Brazil.

So, a lot of human and land resources are tied up in agriculture. It’s vital to the economy, and there’s plenty of product diversity to work with.

Basic developmental issues

That said, despite the apparent strength of Indonesian agriculture, the reality on the ground is that a lot more could be achieved by improving basic practices.

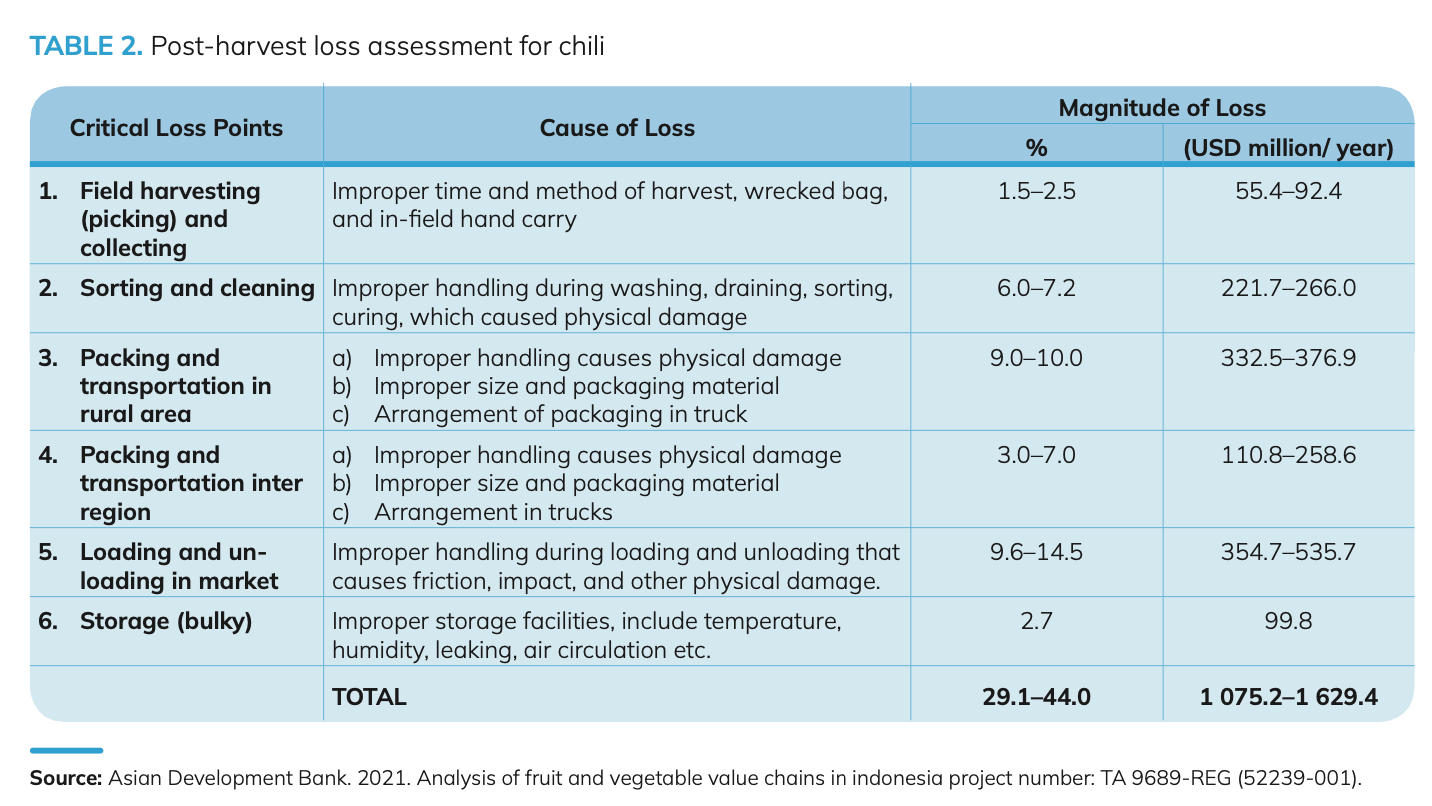

The stat that blew my mind the most during this whole research process: the post-harvest loss of chili ranges from 29.1% to 44%, translating to $1.1–1.6 billion in lost revenue. Losing 10% of your potential revenue just because you didn’t package things properly is insane. And horticulture is the most wasteful part of agriculture: over 30% of the harvest goes to waste, compared to under 6% in crops and under 2% in plantations.

Problems range from farmers not knowing the optimal time to harvest, to wholesalers storing produce in non-ideal conditions. These lead to three types of revenue-related losses across the value chain:

Pure potential revenue loss: A farmer harvests 100% of the crop, but ends up selling only 93%.

Unknown potential revenue loss: Most of these issues are tied to a lack of operational knowledge. And we don’t even know what each value chain participant could be doing better if they had that knowledge.

Margin compression: If product quality is inconsistent, buyers—especially wholesalers and retailers—can negotiate lower prices.

There’s also this wild conundrum: on one hand, 72% of agricultural land is considered “sick” due to a lack of organic matter. That happened because of heavy use of chemical fertilizers, which doubled yields but also trashed the soil. On the other hand, 75% of cow manure is disposed of as waste. Supply and demand are clearly out of sync.

Lack of financing in farming

90% of Indonesian farmers have never accessed financing. A (somewhat dated) study of cocoa farmers found that only 26.8% had access to any financing at all—and most of that came from personal savings.

Two big reasons: high interest rates and requirements that are hard to meet.

Take land rights, for example. The situation in Indonesia is complicated, and there are many cases like this where farmers spend decades fighting for legal ownership of their land. I’m no expert on land law, so I won’t go deep here—but the point is: without recognized land titles, it’s basically impossible to get a loan from a bank.

So, most financing doesn’t come from banks. In fact, 78% is provided by non-bank sources like cooperatives and farmers’ groups.

No financing means no investment. And without investment, it’s incredibly hard to increase land productivity—whether that means using better fertilizer or buying a tractor.

The Roadblocks

Misaligned incentives

Elevarm prioritizes farmers, but it still works with wholesalers, retailers, etc. These groups have differing and sometimes conflicting incentives. Juggling those incentives, understanding how to realign them isn’t easy.

Scaling challenges

Managing such a complex ecosystem—inputs, financing, education, logistics, sales—is capital-intensive and operationally messy. Add in Indonesia’s fragmented rural geography, and that’s a serious challenge. Elevarm is taking on a lot of responsibility in holding it all together.

Margins and unit economics

I get the sense that, given the number of players involved and current productivity levels, making real money from one customer (whether it’s a farmer or a trading partner) isn’t easy. You’ve basically got B2C revenue per client, but B2B-level processes and complexity.

To put it bluntly: it takes a lot of clients, buying a lot of services, to generate significant revenue. I don’t think Elevarm is aiming to maximize profits—but it’s still a tough business to make profitable.

Behavioral change

Changing people’s behavior is hard. Most Indonesian farmers don’t have formal education. Their families have been doing things the same way for generations. Scaling up educational programs and getting each farmer to change their practices takes time, trust, and a whole lot of effort.

External factors

In agriculture, you’re always at the mercy of nature: floods, droughts, pest infestations—you name it. The list of natural disasters in Indonesia is long, and when something bad happens, Elevarm takes a hit. If farmers can’t pay back loans or harvests fall short, there’s less to sell, and the whole chain feels it.

The Upside

Complete integration

If Elevarm can scale and integrate its ecosystem properly, two powerful things will happen:

Network effects will kick in, making the whole system more valuable with every new participant.

Switching costs will skyrocket. Leave the ecosystem, and you could be hit with 30% revenue losses instantly.

That’s likely where the company is headed—and it’s the most exciting part of their long-term prospects.

Inefficiency avalanche

There’s a mountain of inefficiencies to tackle. Packaging alone is a mess—wrong types, wrong sizes, wrong materials. Sure, Elevarm can’t fix everything at once. But there’s a ton of low-hanging fruit: better packaging materials, labor hiring solutions, logistics tools, and more.

And here’s the thing—since Elevarm touches so many points along the chain, they’re in a great spot to uncover these issues from different angles and build solutions that serve all sides.

Government’s activity

Food security is on every government’s priority list, and Indonesia is no exception. For example, in 2022, the World Bank approved a $100 million project to help Indonesia build sustainable, inclusive, and climate-smart agricultural value chains—all aimed at increasing smallholder incomes.

Large TAM

I don’t usually love TAM-based arguments, but in this case, it makes sense. When your B2B market includes millions of potential users in one country—you’re looking at a massive opportunity.

The Takeaway

One of Paul Graham’s essays talks about the idea of schlep blindness. “Schlep” is Yiddish for a tedious or unpleasant task. Schlep blindness is when people overlook ideas simply because they don’t want to deal with the hassle.

He uses Stripe as the poster child for overcoming schlep blindness:

The most striking example I know of schlep blindness is Stripe, or rather Stripe's idea. For over a decade, every hacker who'd ever had to process payments online knew how painful the experience was. Thousands of people must have known about this problem. And yet when they started startups, they decided to build recipe sites, or aggregators for local events. Why? Why work on problems few care much about and no one will pay for, when you could fix one of the most important components of the world's infrastructure? Because schlep blindness prevented people from even considering the idea of fixing payments.

The reason I’m bringing this up is because Elevarm, like Stripe, is going after one of those problems. The kind that’s ugly, complicated, and never-ending. The kind where fixing one thing reveals three more broken things. The kind where you have to fix that thing before you can even move on. Most people will go mad trying to fix all the issues.

It takes serious dedication, skill, and vision to keep going through that mess—to overcome schlep blindness. Stripe did it for payments. Let’s hope Elevarm can do it for agriculture.