It’s Tuesday, and today we’re talking about Eratani, an Indonesian agritech company founded by Andrew Soeherman, Kevin Laksono, and Angles Gan. The company recently secured a $6.2 million Series A led by Clay Capital with participation from TNB Aura, SBI Ven Capital, AgFunder, Genting Ventures, and IIX.

The Product

Not long ago I wrote about another Indonesian agritech startup, Elevarm. Now it’s Eratani’s turn—a similar company, but different.

So what is Eratani?

In a nutshell, it’s a vertically integrated platform that sets out to make farming more efficient and—crucially—fair. It tackles three big pain points:

Access to funding—farmers often don’t have enough capital to buy supplies, upgrade technology, or hire workers. That leads to lower yields and low efficiency overall.

Access to farming supplies and to the end market—farmers struggle to find quality supplies, or the supplies they need are prohibitively expensive. Distributing the end product is tough too, because middlemen, dealing with small batches, can exert a lot of pricing power.

Access to knowledge—another major cause of low yields is a lack of knowledge: what techniques maximize yields, what inputs are best, and so on.

Eratani tackles these challenges not with a single product but with a series of solutions, attacking the problem from different angles. It offers three main services:

EraFarm—helping farmers manage their farms and everything that entails.

EraKios—making quality inputs accessible.

EraMarket—distributing farmers’ harvests.

As with Elevarm, these solutions are designed to support farmers from upstream to downstream, improving both efficiency and resilience.

EraFarm

The biggest piece of Eratani’s offering is EraFarm, and it starts with financing.

Eratani connects farmers with funding sources. But since many farmers have little experience managing money, Eratani first makes them create a purchase plan: what they need, when, and for what purpose. After that, they help farmers make smarter decisions about their newly obtained capital by assisting in budget planning and accounting.

Then there’s insurance, to protect farmers from weather calamities, pests, and other external threats to the harvest.

There’s also an educational component. A team of agronomists guides farmers from planting to harvest, offering advice on cultivation techniques, pest prevention, plant care, and basic technology like soil pH testers.

And Eratani isn’t stopping there. They’ve started moving into IoT products. Last year, the company began testing a Smart Fertilizing Recommendation System, which helps farmers adjust fertilizer levels based on data to improve yields. With the latest round of funding, Eratani plans to dive deeper into physical products, including precision agriculture tools and on-farm mechanization. There are also plans to expand drone and satellite usage and develop agricultural data centers.

EraKios

EraKios ensures that farmers always have access to the best inputs. Through partnerships with input suppliers, Eratani guarantees affordable prices and a reliable supply. Through partnerships with 600 local farmers’ kiosks, it’s built a distribution network. Those kiosk owners can also apply for financing, which further ensures stability.

EraMarket

Through EraMarket, Eratani distributes the farmers’ output. It finds the best place to sell the harvest and sells it. The company works with 70 rice mills and as well as local warehouses to process the crops, then finds buyers among businesses and government institutions. Eratani’s goal is to ensure farmers are paid fairly and that prices on the marketplace are stable enough so farmers don’t feel the pressure of sudden pricing changes.

The Business Model

Eratani’s model is very similar to Elevarm’s. And the key point of similarity is that neither company just created a collection of disjointed products—they’re building ecosystems. Here’s what I wrote about Elevarm:

First, Elevarm is building an ecosystem. Let’s call it a hub-and-root ecosystem (shoutout to ChatGPT for the name). The root in this case is the farmers—they are the foundation of Elevarm’s business. Farmers’ pain points trigger Elevarm’s product development. By developing products for farmers, Elevarm uncovers the pain points of all the supporting players. It then connects the two pain points, thus hitting two targets with one arrow.

[…]

At a higher level, Elevarm plays three interlinked roles:

Enabler—Provides products that empower participants across the ecosystem to do more or be more efficient.

Connector—Bridges fragmented ecosystem players and helps them work together.

Guide—Stays close to farmers and helps them through obstacles.

You could swap in Eratani’s name, and it would still be pretty spot-on.

That said, these aren’t copycat businesses, and I’d highlight three key differences:

Crop selection. Eratani mainly works with rice farmers, while Elevarm focuses on chili farmers. Chili is a much more price volatile crop, less of a necessity, and harder to store. Rice prices are more stable, making it easier to finance farmers and simpler in terms of storage and distribution.

Upstream input strategy. While Elevarm produces some of its own inputs, Eratani doesn’t. Instead, it focuses on building strong partnerships with suppliers. Importantly, Eratani is the sole distributor of the agricultural inputs it sells to farmers.

End product distribution. Elevarm built its own marketplace selling farmer harvests and its own branded products. Eratani doesn’t have a dedicated marketplace and doesn’t sell its own products.

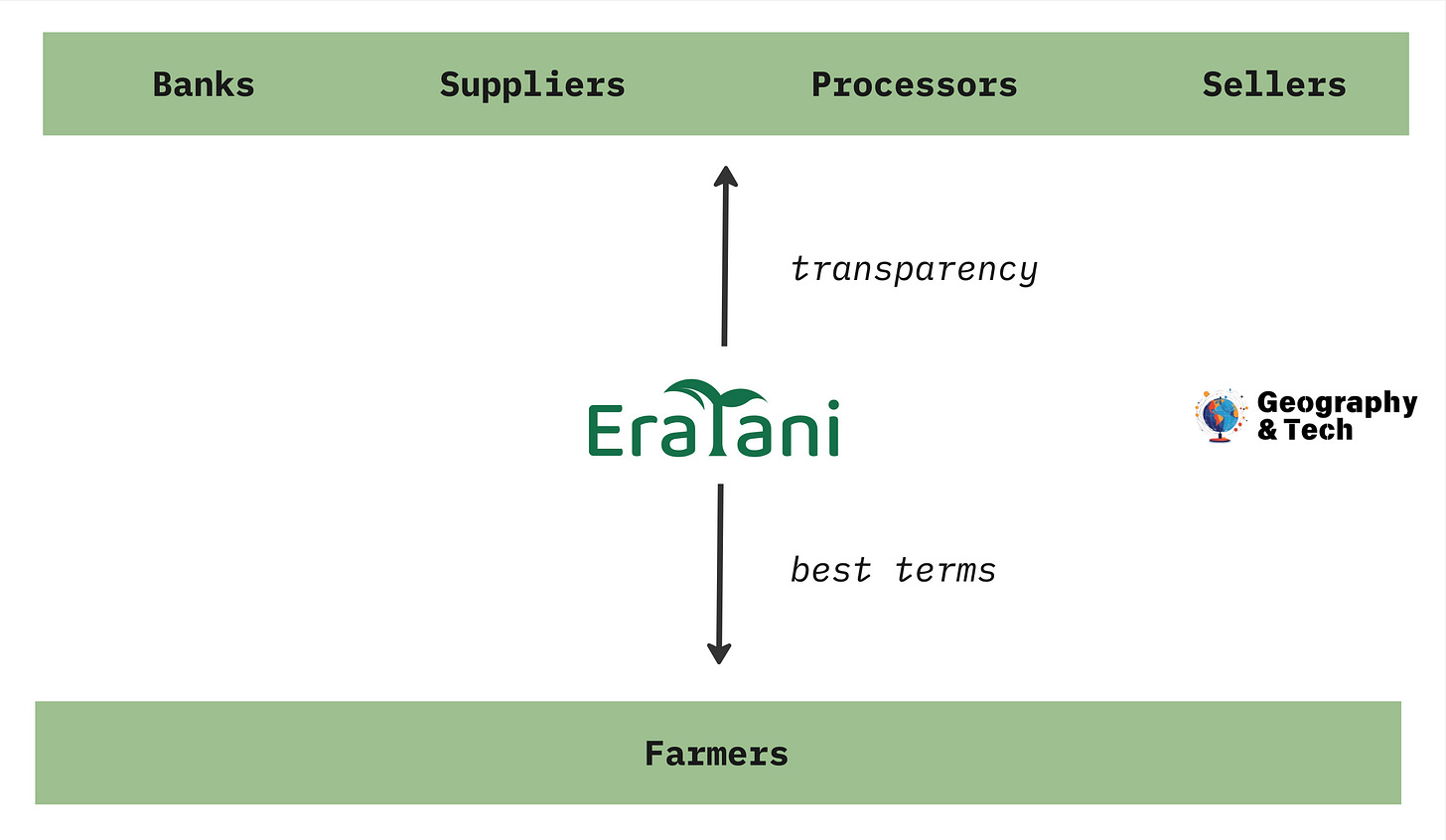

On an unrelated note, another thing that stood out about how Eratani built the business is its focus on transparency.

Eritani is an intermediary between farmers and other value chain participants. Since farmers have limited capital, to maximize its own revenue, Eritani has to sell its services at the lowest prices possible, but still have enough margin. You might say that’s no different from any other business. I would argue it is.

In an industry with stagnant capital markets and thin margins, the only way to create value is by building trust among participants. For two reasons. First, banks, fertilizer suppliers, kiosks—they all have to be confident they’ll get paid. Second, Eratani needs to minimize purchase prices, and one way to do that is by buying in bulk or offering consistent demand for a product or service. With 34,000 farmers working with Eratani, that’s exactly what it can offer: steady demand and bulk purchasing power.

But to convince all these partners to work with Eratani in the first place, it has to provide as much information about the farmers as possible. And it does exactly that. To convince everyone to work with them, Eratani shares a lot of information—product traceability, land ownership, harvest quantity and quality, even farmers’ monthly income. This kind of transparency helps everyone make better decisions.

Eratani has been profitable from day one. Revenue jumped from $20 million in 2023 to $60 million in 2024. Their revenue comes from three main sources:

Loans—they make a 10–12% margin on loans provided by financing partners.

Supply purchases—they earn a 10% commission on input sales.

Crop selling—they buy farmers’ harvests and resell them at a margin.

The Local Angle

National obsession

Rice is a mainstay in Indonesian cuisine. On average, Indonesians consume 181 kg of rice per year, which comes out to about 0.5 kg per day. National statistics show lower figures at around 0.2 kg, but regardless—consumption is among the highest in the world. With this level of consumption and a population of over 280 million, Indonesia is among the leading global rice producers: 34.6 million tons annually, accounting for 6% of the global market, behind only India, China, and Bangladesh.

What’s less expected is that Indonesia is also the largest rice importer, bringing in 4.5 million tons last year. Although most consumption is covered by local production, almost 15% still relies on imports.

So, how does that happen?

Farming practices and geography

This contradiction can be explained by two factors.

First, inefficient farming—driven by both insufficient funding and outdated practices. Around 90% of farmers haven’t accessed financing, and for good reason: interest rates hover around 20% per month. There are a lot of farmers—29 million of them—but most operate on a very small scale: the average family farm size is just 0.6 ha. Small, underdeveloped farms aren’t very productive, which makes banks hesitant to lend. Poor farming practices, inadequate storage, and other issues also lead to significant losses: 11–13% of produced rice is lost post-harvest. Although that’s an improvement from 21% in the past, it’s still basically the difference between needing imports or not.

Second, logistics. Indonesia is a country of 17,508 islands, and logistics are notoriously inefficient. One study found it can be cheaper to ship mandarins from Shanghai to Jakarta than from Jakarta to Padang—despite a sixfold difference in distance. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s neighbors produce enough rice to feed themselves and export surplus, making it easier for Indonesia to import. Around 75% of Indonesia’s imported rice comes from Thailand and Vietnam.

Government support

Recognizing both the critical role of rice and the industry’s challenges, the government has set a goal to become self-sufficient in rice by 2027. To get there, it’s ramping up efforts: large-scale government rice purchases to boost stocks, expanding planting areas, and more. It’s also offering subsidized microloans to farmers and fishermen.

There’s also a degree of price control. When millions produce and hundreds of millions consume a staple crop, you can’t afford major price swings. Rice prices stay fairly stable. That limits farmers’ upside, but it also shields them from devastating price crashes.

The Roadblocks

Price caps

While probably good for farmers, price controls aren’t necessarily great for Eratani. The company still has to buy rice from farmers, but it faces a soft ceiling on what it can sell for. That means input discounts and service fees are the only real places Eratani can widen its margin.

Scaling

As I mentioned in the Elevarm article:

Managing such a complex ecosystem—inputs, financing, education, logistics, sales—is capital-intensive and operationally messy.

And with rice farmers, it’s even tougher simply because there are so many of them. Plus, there’s not much economy of scale when it comes to things like monitoring or on-site education.

Unstable ecosystem elements

Most players in the ecosystem aren’t big businesses. You’ve seen the kiosk photo above—these are tiny operations. Beyond just scaling (i.e., adding more kiosks), there’s the challenge of managing them. Making sure a kiosk or a rice mill delivers reliable service to the rest of the ecosystem isn’t easy when you’re working with micro-enterprises.

The Upside

A giant market

There are over 10 million rice farmers in Indonesia, and Eratani currently works with just over 34,000. Only about 3% of farmers use any kind of agritech solution. In other words, the market is massive—and most of it consists of non-consumers. That’s rare to see.

Farmer lock-in

It’s nearly impossible to leave a well-integrated ecosystem. Especially when farmers see an average 29% yield improvement and a 25% income boost after joining. With Eratani adding new products and improving its data flywheel to enhance on-farm decision-making, those numbers could climb even higher.

Potential for overwhelming importance

Eratani still has a long road ahead, but there’s potential for it to become a critical pillar of national stability. It could evolve into one of the most important cogs in the machine that feeds the entire country. Not today, not tomorrow—and maybe not at all. But the fact that the potential exists is incredibly exciting for the company.

The Takeaway

It’s interesting that two businesses—Eratani and Elevarm—share similar logic and models. I wonder if that’s just a coincidence or if there’s something about Indonesia that uniquely enables companies like this to exist. And these aren’t even the largest players: that title belongs to eFishery. Surely there are examples elsewhere, even if not in agriculture—but for some reason, I haven’t found them yet.