Singapore Data Centers: A Deep Dive into the Hub of Southeast Asian Digital Infrastructure

What makes Singapore so special and what challenges might lie ahead?

Welcome to the first of what I hope will be many deep dives we'll be taking together, exploring the fascinating intersections of technology and geography. In our inaugural post, we journey to the bustling city-state of Singapore, a global titan in the data center industry. I hope you'll enjoy the journey!

And if you would like to receive future articles, then please consider subscribing.

Introduction

It might seem that a country with a land area of just 730 sq km and a consistent 30˚ Celsius year-round temperature wouldn't be the ideal place for state-of-the-art data centers. But, surprisingly, that's not the case in Singapore.

The city-state has long been a focal point for the data center industry, thanks to its conducive regulatory environment, robust connectivity, political stability, and modernity.

The data center industry contributes $1.5 billion to the country’s economy, directly supporting 25,000 jobs, and an additional 1.6 million indirectly. Singapore is home to 74 data centers, as per the data collected from Datacente.rs. On their own, these numbers might not say much, but here's a point to consider: Singapore’s data center market is actually twice as big as the combined market of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

So, let's delve into how exactly Singapore has transformed into this hub for data centers and how geography has played a defining role in the country's success.

Market overview

Singapore has been positioning itself as a data center hub for years. Since 2010, the Infocomm Development Authority (IDA), the country’s telecom regulator, embarked on a mission to develop a data center park (DCP) known as Tanjong Kling. It was envisioned that this park would house more than a dozen data centers. However, the outcome wasn't exactly as expected, with operators lamenting the park’s slow development and an inability to differentiate their offerings from other data centers nearby. But this attempt does illustrate that the country has been involved in the data center industry for quite some time now.

It's challenging to pinpoint when the first data center in Singapore was built, but the country's telecommunications infrastructure has been recognized for its appeal to data centers as early as 2003. This prolonged allure is evident in the data. From 2009 to 2022, 35 data centers have been constructed – or at least, that's how many we have data for. Except for a spike in 2015, there wasn't a huge increase in new data center launches.

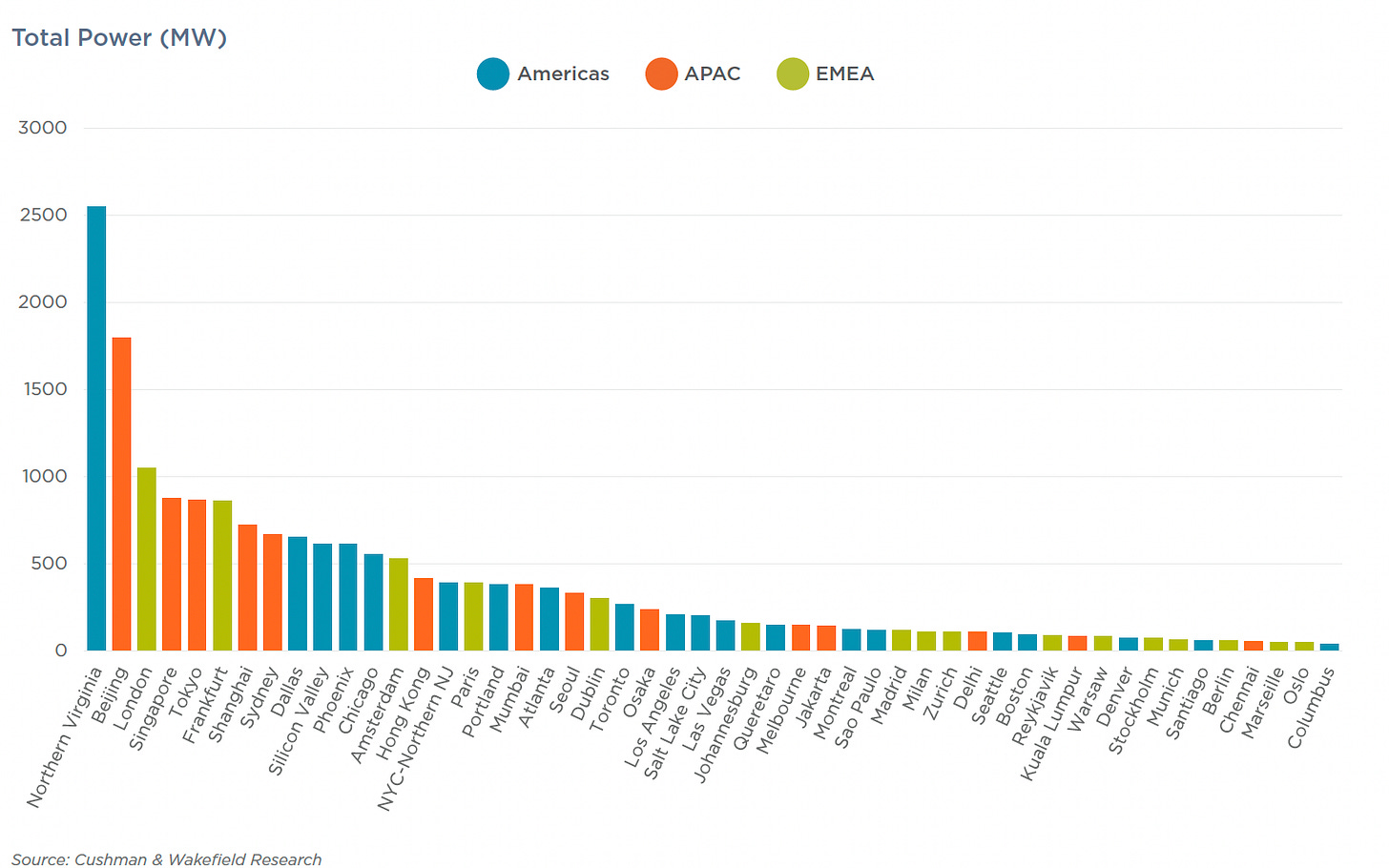

Currently, Singapore ranks as the fourth-largest market by total power capacity, boasting over 800 MW. To put that into perspective, Singapore's data centers generate 0.14 kW per capita, which dwarfs Tokyo's 0.02 kW. Interestingly, there are more data centers in Singapore than in South Korea, a country ten times the size of Singapore. Remarkably, the city-state accounts for 60% of Southeast Asia's total data center capacity.

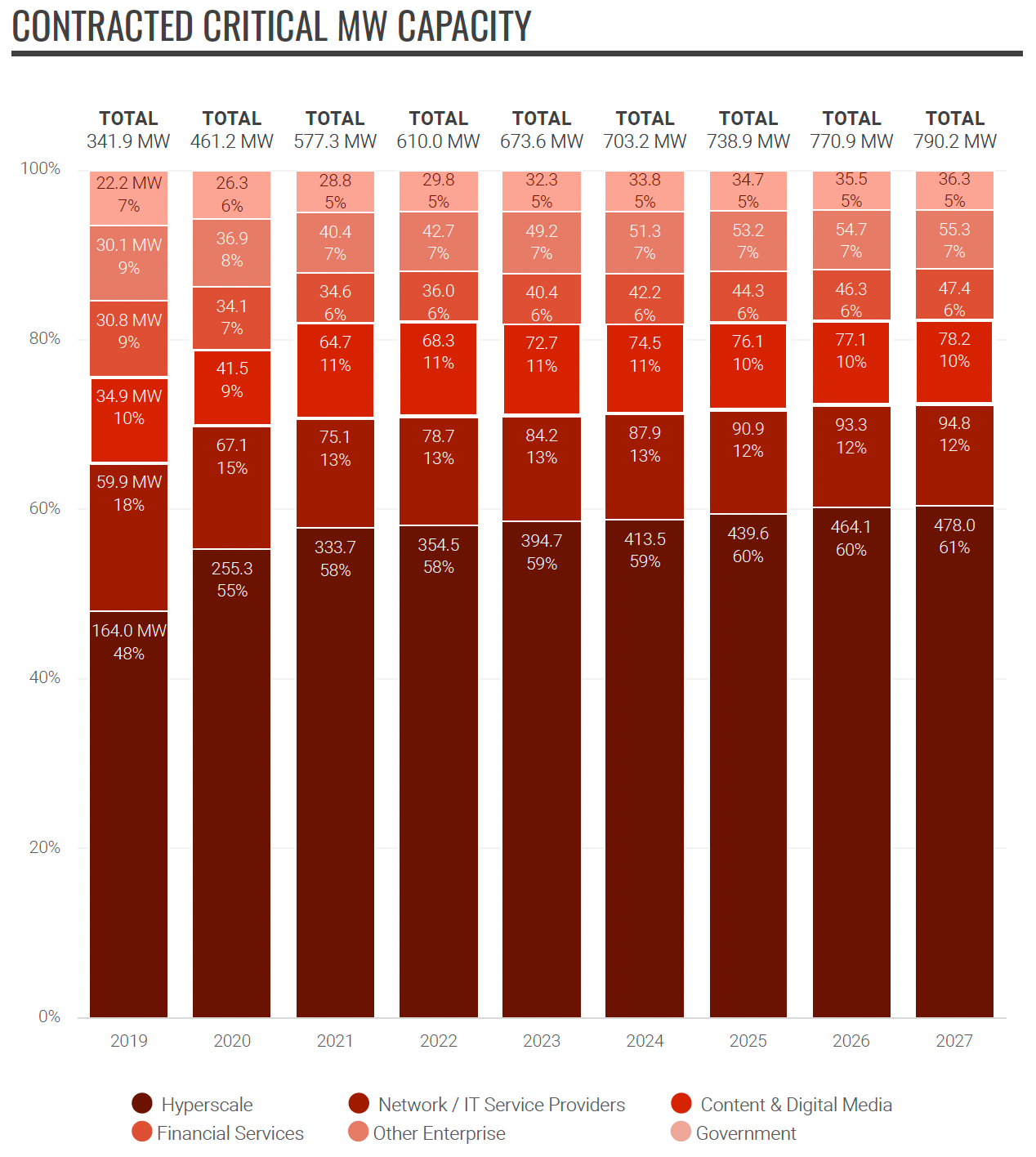

Structurally, mirroring global trends, the demand for hyperscale solutions1 has expanded rapidly, growing from 48% in 2019 to 58% in 2022 in terms of total capacity demand. The shift towards hyperscale cloud data centers is not just occurring among businesses, but government agencies as well. Starting from 2018, the government began migrating its IT infrastructure from on-premises facilities to cloud data centers.

The regional king

Looking at how the industry has been established and why Singapore in particular has been so prominent, a theme quickly emerges. Singapore is looked at as a gateway into Asia Pacific on every level. Consider the following

Over 50% of its export is actually re-export. Hong Kong and the Netherlands are the only other major trade hubs who’s true export is lower that re-export.

Over 50% of its export is actually re-export. Hong Kong and the Netherlands are the only other other significant trade hubs whose true exports are lower than their re-exports.

Out of 7,000 MNCs in Singapore 4,200 have their regional headquarters located here, managing their activities across the region.

Prior to the pandemic, Singapore's airport ranked as the 7th busiest globally, yet the country only ranked 36th by the number of international tourists

Data centers follow the same pattern. Companies establish their data centers in Singapore to bolster their capabilities to serve customers in the Asia Pacific.

Nothing illustrates Singapore's regional prominence better than the influx of capital from the largest technology companies. Their focus on building data center infrastructure to support the entire region is noteworthy. Virtually every major technology company has a data center in Singapore.

AWS was first on the scene, launching company’s first region in Asia Pacific in 2010.

IBM opened their facility the next year citing massive growth in demand for IT services in the region as a reason for expansion.

Google arrived in 2013. The company's explanation for the expansion aptly illustrates the unique blend of Singapore's respected business environment and its locational advantages—being at the heart of this burgeoning colossal market:

Singapore offers an ideal combination of reliable infrastructure (including the region's most extensive subsea cable network), a skilled workforce, and a commitment to transparent and business-friendly regulations. Singapore also has a vibrant internet economy and is located in the center of one of the fastest-growing internet markets in the world. Millions of users in Southeast Asia are coming online every day for information and entertainment, new business opportunities, and better ways to connect with friends and family, near and far.

The same year, Oracle’s 385 000 sq ft facility commenced operations, with the company explicitly stating they would meet Singapore's regulatory requirements in data management. Singapore's early-mover advantage in data protection clearly paid off

Alibaba not only expanded to Singapore by building new data centers, but also established its regional headquarters for cloud operations. Sicheng (Ethan) Yu, Vice President of Alibaba Cloud, commented on the decision saying:

We are seeing healthy demand for cloud-related data management services in Singapore because of the ease of doing business, comprehensive transport and telecommunications connections and robust intellectual property regime. The stable geopolitical climate and abundance of highly skilled talent are advantages too.

Finally, the most ambitious data center project in Singapore's history opened its doors in 2020 — the colossal 1,819,000 sq ft facility built by Meta, then Facebook. Considered one of, if not the biggest data center in the world, it operates entirely on renewable energy, like other facilities run by the company.

What makes Singapore stand out?

Data centers generally prefer to locate near their customers for three primary reasons.

First, it reduces latency, which is the time it takes for data to travel from one point to another. The closer the data center is to the user, the lower the latency. This improvement substantially enhances the user's ability to run data-intensive applications and services such as video streaming.

Second, proximity improves network reliability. The farther the data has to travel, the more likely it is to encounter issues like packet loss, which can degrade the quality of service.

Third, it reduces costs. Cloud providers charge for data transfers out of their data centers. As a customer, depending on where you're transferring data from and to, the charges vary.

But you might ask: If distance is so crucial, why is there any data center concentration at all? Shouldn't data centers be distributed evenly among the most data-consuming nations? That's where Singapore's unique advantages come into play.

When scrutinizing what's important for a data center operator in choosing the ideal location, we quickly encounter a diverse set of circumstances to consider and questions to answer:

Are there any potential customers?

How good is the connectivity?

Is the country politically stable?

How high is the risk of an earthquake?

Will there be reliable energy?

etc.

Remarkably, Singapore stands out in practically every aspect an operator might consider.

The Market

Just about every product needs a sufficient market to be successful. The larger the market, the greater the success. The data center market is no different. For data centers, market "bigness" manifests itself in three ways:

Population size — more people means more data to be stored and analyzed.

The number of enterprise-level customers — their sheer size implies the need for advanced data storage.

The size of data-consuming/producing industries — such as the financial sector and digital media.

How’s Singapore doing?

Though Singapore might lack in population size, it clearly compensates with its robust corporate sector.

With 4,200 regional HQs and its prominence as a financial hub, it's practically inevitable for Singapore to be a significant data center hub.

Moreover, Singapore is favored more by industries that either require low latency or are location-sensitive. Such industries have been the country's staples, and their proximity demands are continually growing. For instance, low latency enables functionalities like high-speed trading and fraud detection, which are crucial for financial institutions operating in the country.

They are practically compelled to build out enough data center capacity to manage their day-to-day operations and provide top-tier client service efficiently.

In this context, the universal digitization trend is making physical location more important than ever.

Robust connectivity

Undersea cables are the backbone of global connectivity, carrying over 99% of the world's data across continents. Through these cables, data is transmitted swiftly, efficiently, and reliably.

Locating data centers near undersea cable landing points offers several advantages:

It reduces latency.

It increases bandwidth by connecting directly to high-capacity cables.

It provides resiliency and redundancy, as data can be rerouted in case of issues with one of the cables.

How’s Singapore doing?

Situated at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, bridging the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Singapore has been a hub of connectivity for many years. Once vital for trade, it's now a pivotal point for undersea cables. Singapore ranks among the most well-connected nations globally, boasting 25 operational cable landing stations.

Singapore's connectivity continues to improve, with 14 projects currently in the pipeline. Notably, Google and Meta are collaborating to link the U.S. West Coast with Southeast Asia, and more specifically, Singapore and Indonesia. This project is anticipated to bolster data capacity between the regions by 70%. Several cables are being developed by Chinese state-owned telecom companies, one of which is designed to connect Hong Kong, Hainan province, Singapore, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and France.

The adoption of 5G also drives the growth in data center demand, both on the consumer and business side. The impacts are threefold.

Firstly, in theory, 5G will offer faster speeds and lower latency, facilitating more data-intensive applications, from augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to the Internet of Things (IoT).

Secondly, 5G aids the transition towards edge computing, where data processing occurs closer to its source, resulting in reduced latency. The growing demand for edge computing necessitates the construction of more edge data centers.

Thirdly, 5G enables the development of new consumer and business applications, creating a positive feedback loop: the more new applications emerge, the more data is consumed, leading to more data centers being built. This improves infrastructure, which in turn opens up more opportunities for new application development.

Singapore is at the forefront of the global 5G race, with the local telecommunications operator, Singtel, announcing in 2022 that it has achieved 95% standalone 5G nationwide coverage, surpassing the local government's initial aim of full coverage by 2025. Singapore is not the only nation with ambitious 5G goals. According to Ericsson, the 5G penetration rate in Southeast Asia is expected to reach 48% by 2028.

Political stability

Investing in a data center is not a small financial endeavor. The estimated cost to build a data center ranges from $7 million to $12 million, and the operational expenses can add an additional $10 million to $25 million. This means constructing and running a 10MW data center for five years could cost anywhere between $120 million and $245 million. Suppose it takes ten years for such a project to break even; that's a significant investment and a considerable period to recuperate your expenditure. The last thing any investor would want is for political instability, corruption, or foreign sanctions to jeopardize the investment.

How’s Singapore doing?

It would be a stretch to call Singapore a flourishing democracy. It ranks 70th in The Economist Democracy Index, 86th in the Democracy Matrix, and 127th in the Freedom House rankings. In general, countries with lower democratic scores may exhibit political instability due to regular disruptions or even pose business risks in authoritative dictatorships.

However, Singapore appears to be a rare, if not unique, exception to this trend. The People's Action Party has been leading the country since 1965, consistently maintaining a pro-business and anti-corruption stance. This has been bolstered by an efficient, transparent legal system and good relations with all the significant economies globally. Singapore ranks 5th in the Corruption Perception Index and boasts one of the lowest crime rates globally, further reinforcing its appeal to business investors.

Business environment

Everybody wants to do business in a safe, efficient and productive business environment. Such an environment not only draws businesses but also contributes to infrastructure development by taxing those businesses. In this scenario, high-quality infrastructure, especially robust connectivity, fuels the growth of the data center industry. This enhancement of the infrastructure, in turn, attracts more businesses, creating a virtuous cycle of growth.

How’s Singapore doing?

The Singaporean government has executed two pivotal strategies propelling the country to its current global standing.

Initially, unlike South Korea and Taiwan, Singapore focused on attracting foreign direct investment.

In 1961, the establishment of the Economic Development Board facilitated the growth of the Jurong Industrial Estate, a manufacturing hub that initially focused on export-oriented, low-value-added products2. The Board also set up training programs to upskill workers and acted as an intermediary between investors and government bodies.

Moreover, the introduction of the Economic Expansion Incentives Act in 1967 offered tax incentives to pioneering industries for up to 15 years.

Singapore also houses three export processing zones, with Jurong Industrial Estate being the first one, providing various benefits such as tax suspension and 140-day free storage for transshipment/re-export cargo.

Secondly, Singapore has developed a business environment renowned for its effectiveness. he nation consistently ranked at the top of "Ease of Doing Business" indices. What’s so great about Singapore’s business environment, you might ask. Well:

Singapore has no capital gains tax, one of the lowest corporate tax rates in the developed world, and an income tax rate capped at 22%.

Additionally, Singapore provides robust incentives, like the Pioneer Industries (Manufacturing), which grants tax exemptions to producers of innovative products within the country.

Investment in human capital is also a priority for the Singaporean government. It offers social programs focused on reskilling and upskilling. A national initiative, SkillsFuture, grants every Singaporean aged over 25 a S$500 credit to offset course fees for a variety of skills-related courses. In 2021 alone, 247,000 people utilized their credit.

In essence, Singapore's thriving business environment is the bedrock upon which the nation has been built, ensuring its continued prosperity.

Technological development

From the standpoint of data centers, we can perceive technological development in two facets. We've discussed the first facet, technology as infrastructure, primarily concerning connectivity. The second facet views technology as a client, with technology companies and governments striving for citizen betterment through technology being the primary clients of data centers.

How’s Singapore doing?

In 2018, Singapore's Economic Development Board reported that 80 of the top 100 tech firms have a presence in the country. Virtually every global cloud computing company operates a data center in Singapore. What makes Singapore unique is its fusion of economic stability and political neutrality.

Global giants like Google and Huawei have data centers in Singapore, notwithstanding their geopolitical hurdles elsewhere. Google has no data centers in China, Huawei ain’t building its facilities in Brussels any time soon either. Yet, they both find Singapore an agreeable and viable location.

And then there’s government demand. Singapore takes pride in its status as Asia's smartest city, as it probably should.

Under the Smart Nation initiative, the government has launched numerous successful programs. For instance:

LifeSG, an application offering access to over 40 government services, from reporting neighborhood maintenance issues to scheduling virtual meetings at the Ministry of Law.

Singpass, a biometric-enabled gateway to government e-services. Through Singpass, residents can sign documents, perform digital banking, or manage insurance.

The Smart Nation Sensor Platform (SNSP) is an IoT utility platform employing sensors deployed throughout Singapore's homes and buildings for local infrastructure management. It aids homeowners in detecting water leakages and uses lamp post sensors to collect data for designing safer footpaths.

Energy availability

Data centers are notoriously energy-intensive. In fact, electrical costs can account for up to 50% of all operational expenses, primarily due to the need for cooling. Along with costs, data center operators also prioritize energy security, encompassing both reliability and independence.

How’s Singapore doing?

Not great. Businesses pay $0.32 per KW, a figure significantly higher than the $0.1 charged in neighboring Malaysia. However, cost is not the primary concern. By 2030, data centers are forecasted to account for a hefty 12% of Singapore's total energy consumption. This substantial energy demand arises not only from the size of the industry within a relatively small country but also from the consistently high daily mean temperatures, which seldom fall below 26.8˚ Celsius. Given that data centers operate optimally at around 21˚ Celsius, a significant proportion of energy consumption goes towards cooling.

Therefore, Singapore grapples with the double challenge of high energy prices and increased cooling costs due to the persistent high temperatures.

Moreover, energy independence is a concern. Singapore generates 90% of its electricity from natural gas, which it must import from Indonesia and Malaysia as it doesn't produce it domestically.

In summary, data centers in Singapore face the predicament of paying for expensive energy, which is generated from imported hydrocarbons, and require more of this energy for additional cooling due to the country's high ambient temperature.

Land availability and prices

he average size of a data center is around 100,000 square feet, while the largest ones can easily exceed 1 million square feet.

The average size of a data center is 100,000 square feet, while the largest ones can easily exceed 1 million square feet. Four of five biggest data centers are located in the middle of nowhere: two in Inner Mongolia, one in Utah, one in Nevada. You get the point: empty land, means cheaper land, means bigger data center.

How’s Singapore doing?

Well, not of that applies to Singapore. The combination of a limited land area and high demand for that area invariably drives up prices, even amidst a global downturn.

Singapore has made concerted efforts to address its space constraints. Since 1965, the country has expanded its land mass by 25%. Nonetheless, it remains one of the smallest and most densely populated countries globally.

Environmental risks

Earthquakes pose the most significant natural disaster threat to data center operations. While there are technologies available to mitigate the impact of earthquakes, operators would certainly prefer to avoid regions prone to such events.

How’s Singapore doing?

Fortunately, Singapore sits on the Eurasian Plate, well away from the Pacific Ring of Fire, which is one of the main earthquake belts in the world. Although Singapore can experience tremors from earthquakes in neighboring Indonesia, it is largely spared from the direct impacts of these natural disasters.

However, the prospect of rising sea levels in the future could pose a challenge. But in such a scenario, the future of the data center industry might be the least of our worries.

Data protection

Data protection laws can impact the data center industry in two ways. First, robust data protection measures ensure that a client's data is stored safely and securely with the data center operator. This scenario creates a win-win situation for both clients and operators. Second, certain laws, like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU that data be stored within specific jurisdictions. While this might not be particularly beneficial for businesses that now need to be more concerned about data storage, it is certainly advantageous for the data center industry, as data centers become a mandatory requirement.

How’s Singapore doing?

Singapore took the first approach.

The country was one of the earliest in Southeast and East Asia to pass a comprehensive data protection law, the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), in 2012. Like GDPR, the PDPA requires organizations to obtain individuals' consent to collect and use data and imposes penalties for non-compliance.

While the PDPA doesn't mandate that companies store their data locally (which would provide a direct stimulus for new data centers), it helps set the right tone. If a company wants to reassure its clients that their data is protected, the PDPA provides a strong regulatory framework to support this claim.

Outside drivers

Finally, there are external drivers. What if a country could not only support its own data storage and computing needs but also serve as a hub for its neighboring countries and the broader region?

How’s Singapore doing?

The accelerated digitalization wave sweeping the Asia Pacific region has undoubtedly been a critical growth driver for the industry.

According to a report by Bain & Google, in six Southeast Asian countries (Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia), the number of internet users has increased from 360 million to 460 million from 2019 to 2022. During the same period, the region's digital economy has ballooned from $102 billion to $194 billion in gross merchandise value (GMV), and it is expected to continue growing at a rate of 20% per year until 2025.

The region's digital economy directly employs 160,000 people and indirectly supports 30 million jobs. Depending on the country, the digital economy already contributes 5-10% to the local GDP. As digital GMV is growing more than twice as fast as GDP, the sector's significance is only expected to increase.

Challenges

It’s not all rose colored glasses in Singapore. The country currently grapples with at least four issues that need addressing to sustain its data center dominance.

The effects of the moratorium

In 2019, the Singaporean government imposed a moratorium on new data center construction, citing the rapid expansion of the sector as incompatible with the country's climate and sustainability commitments.

While these restrictions were lifted in the second quarter of 2022, limitations remain. Firstly, there's an annual cap on the number of data centers that can be built. During the pilot phase of 12-18 months, only three data centers were to be approved, with their cumulative capacity not exceeding 60MW.

Secondly, the government encourages responsible and sustainable data center operations. The prerequisites one must meet to build a new facility are quite extensive. Among other requirements:

The maximum Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) should be 1.3 or less.

The facility should meet the Building and Construction Authority — Infocomm Media Development Authority (BCA-IMDA) Green Mark Platinum standard. To achieve this certification, a data center must comply with a multitude of cooling, water, and energy efficiency standards, essentially embodying the pinnacle of data center efficiency.

The applicant must demonstrate how their proposal would bolster Singapore's position as a data center and technology hub, and what broader economic value it brings.

In July, the government allocated around 80 MW of new capacity to four data center operators, in response to 20 proposals. The demand is strong, but the barriers to entry are remarkably high.

Vacancy and costs

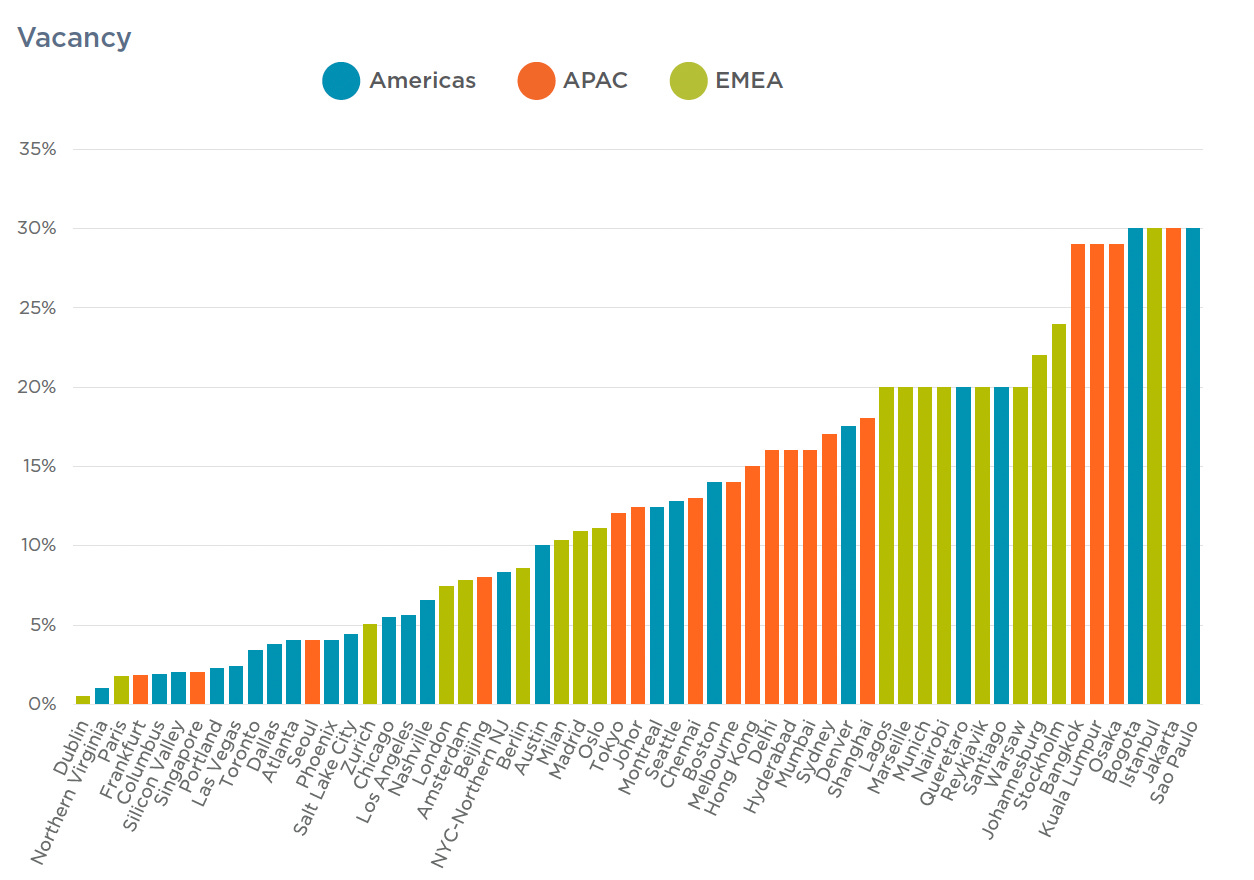

The moratorium, limited land availability, and robust regional demand have led to record low vacancies in data centers, sitting at 2% in 2022.

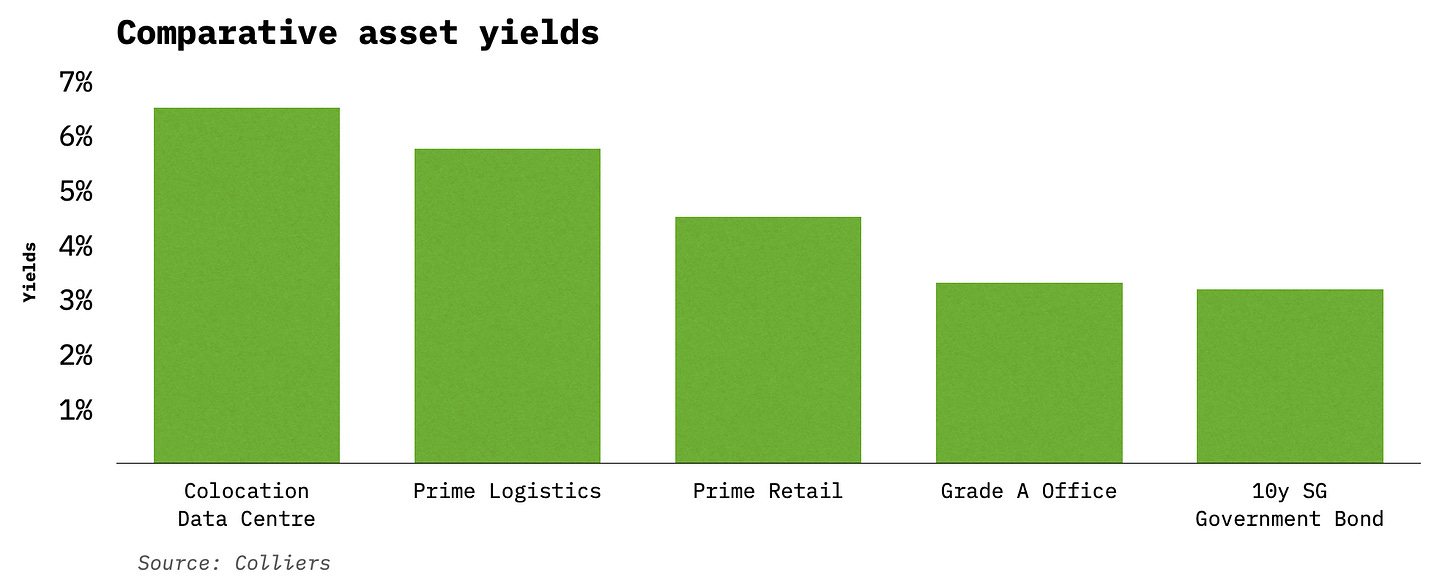

Such conditions do not support affordability. According to a report by Colliers, in 2021, colocation rents varied from $203 per KW/month for hyperscale tenants to $617 per KW/month for retail tenants. This makes Singapore the most expensive location to rent rack space. The restricted supply has been pushing rents up 20% to 30% annually, and with current constraints on data center expansion, there are no signs of price stabilization. Plus, as we've established earlier, electricity in Singapore is far from cheap.

It might be compelling to look at this as a great thing for investors, but not so great for businesses. And there is no better real estate in Singapore you can invest in.

However, the construction costs are also on the rise, with an 18% increase recorded in 2021 alone. And then there's the carbon tax issue to consider. Through 2023, it stands at $3.77 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent, but by 2026, it's set to skyrocket to $33.82 - a tenfold increase in just three years. This steep rise will undoubtedly add to the financial burden borne by the data center industry.

Competition

Singapore, long being a dominant player in the data center industry, has seen recent challenges affecting its preeminence. The government's ban and subsequent restrictions on the construction of new data centers have prompted businesses to explore other geographies. Emerging alternatives have been found in neighboring regions like Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and notably Johor Bahru.

Johor Bahru, just across the Singaporean Strait, is becoming an attractive location for data center investment. The city offers ample land and energy resources and holds the advantage of being a free trade zone. Its proximity to Singapore gives it an edge, attracting investors looking for strategic locations with plenty of resources

There is also a growing trend of decentralization in the hyperscale cloud industry, which may further diffuse Singapore's centrality in the regional data center map. Hyperscalers, having deployed their capacity in core markets like Singapore or Hong Kong, are now looking towards emerging markets. Spurred by rapid digitalization and improved connectivity, these hyperscalers are likely to continue expanding their capacity, filling in the infrastructure gaps and getting closer to their end-users.

The organic demand for data centers in Southeast Asia also paints a challenging picture for Singapore's long-term dominance. With the demand growing by an impressive 10-15% per year, the data center industry is set for a vibrant future. However, it may become increasingly difficult for Singapore to maintain its dominance in light of this robust regional growth.

In summary, while Singapore has long been a cornerstone in the data center industry, internal and external factors are causing a shift. While it will continue to play a significant role, we can expect to see a more distributed landscape in the future, influenced by emerging markets and the ongoing trend of decentralization.

Energy

Singapore has always been a leader in the drive towards a more sustainable future, and its efforts in green energy and sustainability are praiseworthy. The city-state is guided by the ambitious Green Plan 2030, which has a myriad of targets ranging from expanding the land area of nature parks by over 50% in ten years, to a four-fold increase in solar energy deployment from 2020 to 2025. The ultimate aim is to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, with plans even to utilize hydrogen for half of its energy generation.

Moreover, the data center industry is at the vanguard of this sustainability movement. The efforts of the industry go beyond just utilizing renewable energy to power the large facilities; they also encompass innovative projects that embody the principles of sustainability.

Keppel's floating data center project is probably the most ambitious green initiative in Singapore's data center industry. The ingenious design involves modular units that can be scaled up or down based on demand and recycled once they've reached the end of their life cycle. Given its near-shore location, the project aims to leverage seawater for cooling purposes, thereby increasing cooling efficiency by a whopping 80%.

Despite these promising steps, it's important to acknowledge that Singapore still has a significant journey ahead in its quest for sustainability. The challenges are numerous, but the commitment to a greener future and innovative projects like Keppel's floating data center are positive signs that Singapore is moving in the right direction.

Hyperscale data centers are massive data centers built for or by cloud providers or large tech companies with their expansive needs for scalability.

EDB was very creative in promoting the newly established industrial park. As an example, they held ceremonies when investors signed agreements, when the ground broke for a new project, and for official opening ceremonies as well. That helped drive hype in the media and by late 1960s 181 factories were in production.